The Church today is living in a time of saints, and of martyrs, and I suspect we shall see rather more of both in the coming weeks and years

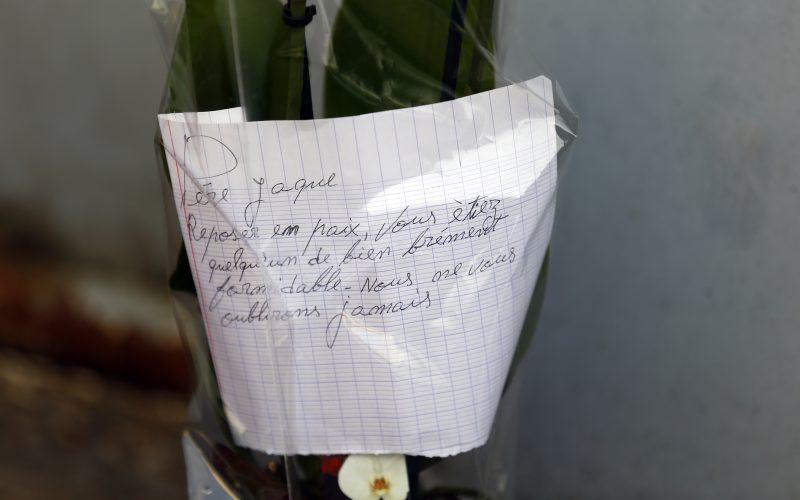

Fr Jacques Hamel died a martyr’s death. Of this there can be no question. The 85-year-old priest was at the altar offering the sacrifice of Mass, the moment in which the Church makes present the sacrifice of Christ’s body and blood for the salvation of the world, and his blood was literally mingled with that of Christ. The savagery of the attack has left the secular world, and many in the Church, stunned. While there is a natural human revulsion to such crazed brutality, the Church was founded on such acts of bloody witness to the faith.

As Damian Thompson rightly pointed out for the Herald yesterday, what appears as an almost unimaginable horror in France is, tragically, a reality of daily Christian life for those living in Iraq and many other places in the Middle East. I say tragically; any loss of human life is surely a tragedy, but what the Church has proclaimed, from the moment of its foundation, is that the martyr’s crown is glorious. The willingness to receive death for the faith, rather than to deal it out, it the counter-intuitive core of the Christian witness of radical love, and what sets it apart from the pagan religions against which it was first proclaimed. One of the earliest legends concerning the conversion of St George is that, as a soldier in the Imperial Court, he converted after witnessing a Christian accept a sentence of death rather than recant their faith. This, he is supposed to have observed, is true courage to shame any soldier.

When Oscar Romero was beatified last year, many thought his cause was long overdue. Here was a man who had been killed in the very act of saying Mass, surely this was a martyr’s death. Others were more sceptical, not of the late Archbishop’s courage or holiness, but of his prudence by continuing to appear in public despite knowing the great risk of being killed for having spoken out against the violent oppression of the people; the question was asked: was his murder was really in odium fidei, or if it was more personally directed? Wherever you happen to be on that question, there is no such doubt in the case of Fr Hamel: he was killed simply and solely because he was a priest, in a church, offering Mass. The emerging accounts of the murders having preached their rationale from the altar immediately before or after martyring the priest only underscores the immediacy of their hatred for the faith.

These men were not dispossessed youths, acting out against social exclusion or economic disadvantage; they were violent adherents to a violent theology. They killed in the name of their god and Fr Hamel died in the very act of invoking the sacrifice of life.

Haras Rafiq, the managing director of the Quilliam Foundation, has described the attack as a turning point in so-called radical Islam’s war against what they see as the Christian West. “What these two people today have done is … shifted the tactical attack to the attack on Rome … an attack on Christianity.” ISIS have previously made clear that their greatest objective is the conquest of Rome, and the overthrow of the Holy See, as the global heart of the Christian faith.

While I am sure that the Vatican proper, and the person of Pope Francis, will now be under closer security than ever before, the Church is a global soft target. There are thousands of Fr Hamels across the world, and an even greater number of those faithful who joined him for what became his viaticum Mass. They cannot all be protected against such attacks. If the target is the Christian faith, than every Church, every priest, nun, man, woman or child in the pews is of equal value. One thinks of the horror that could easily be visited upon the hundreds of thousands of young pilgrims currently on their way to World Youth Day in Poland.

In the immediate hours after the attack in Saint-Etienne-du-Rouvray, I was asked by someone if it made a difference that, so far as we know, Fr Hamel was not offered the chance to renounce his faith to save his life. My short answer was “of course not.” But it is worth making the point that, through baptism, we each of us have accepted the faith, a faith the holds out two promises to us: heaven and the cross. Martyrdom has, for many Christians, become a mythic concept. In fact, it is an immediate and essential part of the faith and of the Church’s mission to spread it. To be killed for being a Christian is to be a martyr, a possibility we are each called to accept.

When St John Paul II was canonised, many people remarked that it was strange to think we had lived at the same time as a saint. The Church today is living in a time of saints, and of martyrs, and I suspect we shall see rather more of both in the coming weeks and years. But the truth of the matter is, the Church has always been

Fonte: Catholic Herald